Tech Savvy and Safe

This article written by Siveco China’s General Manager, Bruno Lhopiteau was initially published Shanghai Business review in January 2013.

To strengthen their risk prevention practices, foreign firms in China should take heed of the technological solutions being used by domestic companies.

Occupational safety, for both company employees and the general public, remains a perennial issue in China. Multinational corporations (MNCs) tend to approach the problem from a Western perspective, with tools designed to solve Western problems and with the belief that business operations in China will simply become more mature with the passage of time. This perspective usually fails to deliver better practical results, and has proven to be hugely inefficient. On the other hand, their Chinese counterparts, who started without any safety culture to speak of, are innovatively dealing with problems by using modern technology rather than decades-old Western wisdom.

Cautionary Tales

Safety issues have remained at the top of the agenda for several years now, and have attracted attention from the central government while receiving wide coverage from traditional and social media. Nevertheless, government and corporate initiatives, most of which call for more frequent audits, have not managed to significantly reduce the number of new incidents.

China’s fire safety record is poor. Those in the profession can recall countless locked fire-doors and disconnected alarm systems, as well as instances involving cartons of prestigious cigarette brands being offered to fire safety officials as bribes. Leading certification firm Bureau Veritas reports that its fire protection system audits, conducted in new facilities, show 10 per cent of systems not working at all and another 40 per cent with major non-compliance. Years have passed, but the statistics have not improved.

Major elevator mishaps and escalator accidents have also been reported in buildings across the country, often involving well-known Western brands, with the causes usually traced to basic design or maintenance problems. Accidents on construction sites have led relevant ministries to call for more onsite audits. Many issues are linked to the practice of “cascading subcontracts”, in which vital responsibilities are eventually subcontracted all the way down to farmers working with their own makeshift tools. Food safety is perhaps the scariest issue, with criminal cases making headlines. Problems with the cold chain, i.e. the refrigeration systems in warehouses, trucks and shops, are much less visible to the public but are well-known to food industry professionals. The list goes on and on, across a wide spectrum of industries.

As fond as local and international media are of blaming the government, a solid regulatory framework has already been put in place, as in the case of fire safety. Industrial best practices are also well-documented, as with equipment inspection procedures. Aside from the government’s willingness and capacity to regulate, it is the practical enforcement of regulations and best practices than remain the biggest challenge in China.

Obstacles to Enforcement

Specific obstacles include the sheer size of the country, the large number of sites and facilities, and the number of workers involved. Fast economic growth has greatly contributed to the problem, with hundreds of highly complex projects running simultaneously across China. At the same time, the country is facing an acute skills shortage across disciplines, from qualified workers to experienced managers, as well as high turnover due to competition for projects.

The lack of a structured methodology to working out and solving problems is a major challenge. A classic example would be the inability of most technicians to follow step-by-step instructions. Their approach often involves starting from the end, finding that it does not work, going a few steps back, improvising a bit, calling on some colleagues for input, and then perhaps finding a quick-fix. The problem remains hidden until it appears again, sometimes with disastrous results. The right paperwork will often be properly filled-in, in full compliance with administrative requirements, but leaving no trace of what really happened.

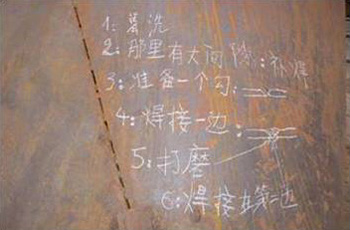

One practical work-around, which we use on construction sites, consists of feeding the workers with one instruction at a time, and confirming execution of each step before moving on to the next one. This is sometimes done by writing each step with chalk on the nearest available wall or on sheet metal. Such a visual and tangible approach helps gain the workers’ attention and structure their actions.

Simple approaches to giving workers instructions, like writing with chalk on walls in construction sites, can ensure clear communication and avoid short-cut tactics.

The traditional safety methodology, advocated by Western firms and backed by decades of experience abroad, consists of ensuring compliance with a strict recording system, normally resulting in extensive paper procedures. Although such a paper-based approach actually fits in well with the Chinese bureaucratic experience, it delivers very little improvement in practice. The neat, colourful company policy folders are often left to collect dust on the site manager’s shelf, with no assurance whatsoever that those procedures are actually being followed on site, or that the reports are accurate. This leads to a multiplication of spot checks- the government “solution” for safety accidents – breeding the need for a massive support organisation, with auditors, administrators, supervisors and clerks to handle papers and spreadsheets. Inevitably, the question arises: who audits the auditors?

We believe that the traditional Western approach is flawed, as it fails to address the Chinese situation. In such conditions, questions remain as to how to implement best practices, how to ensure regulatory compliance, and how to prevent risks, on a large scale, with a low-skilled workforce and under-qualified middle-management?

Technology As an Enabler

In the past few years, large Chinese companies such as property developers- among the worst offenders when it comes to safety- have become keenly aware of the problem. Realising that traditional methods inspired by the West were not working in China, many such firms have developed unconventional solutions.

As shown with the system of using chalk handwriting on sheet metal, a tangible object can be used to create a structured, fool-proof way of working. Think of road traffic: laws, training, and policing are all in place, yet cars keep crossing the designated lines. Add concrete dividers, and the same street becomes impeccably disciplined. More advanced technologies can be used for the same effect.

Mobile technologies are so prevalent today that even construction workers and cleaners use smartphones. Technicians at Greenland, a property developer that manages several ultra-high buildings, use their mobile phones to receive step-by-step instructions and to report on each step. Mandatory scanning of Quick Response codes on assets or inspection points, and automatic GPS and time recording, ensure that the worker has actually been there. Non-compliance and risk areas are immediately reported into a central system. At the group level, managers interact with a large touch-screen panel, displaying risk-level indicators in the various regions, while supervisors on the move use tablets. Great Wall, another developer, has achieved Rmb30m in annual labour savings in the first year, eliminating entire layers of administration and reallocating resources to risk prevention and value-added jobs such as energy savings.

These innovative solutions, designed in China but also benefiting from experience in the West, act as a structuring tool to motivate workers, to train them on-the-job, to organise them around clear processes and to gently enforce those processes from top management down to individual workers. As the system is meant to assist workers, not to replace or control them, their reactions are usually very positive.

The results obtained so far have been very favourable, with the occasional hiccups but also continuous enhancements. Systems have been deployed since 2009 to hundreds of sites and thousands of mobile users, providing constant feedback for improvement. It is true that indirect savings, which are risk related, are hard to compute because we are talking about preventing uncertain events from occurring. Having said that, experience in China shows a typical ten-one ratio between indirect and direct costs in property management (indirect costs are those losses due to problems).

The most apparent benefit is a company’s immediate reallocation of resources to risk prevention, while in terms of communication, we have seen the fancy touch-screen display take centre-stage at management meetings, official visits, and internal training sessions. As a result, the company’s focus on risk prevention and best practices is made obvious to all stakeholders.

Tags: safety、risk prevention