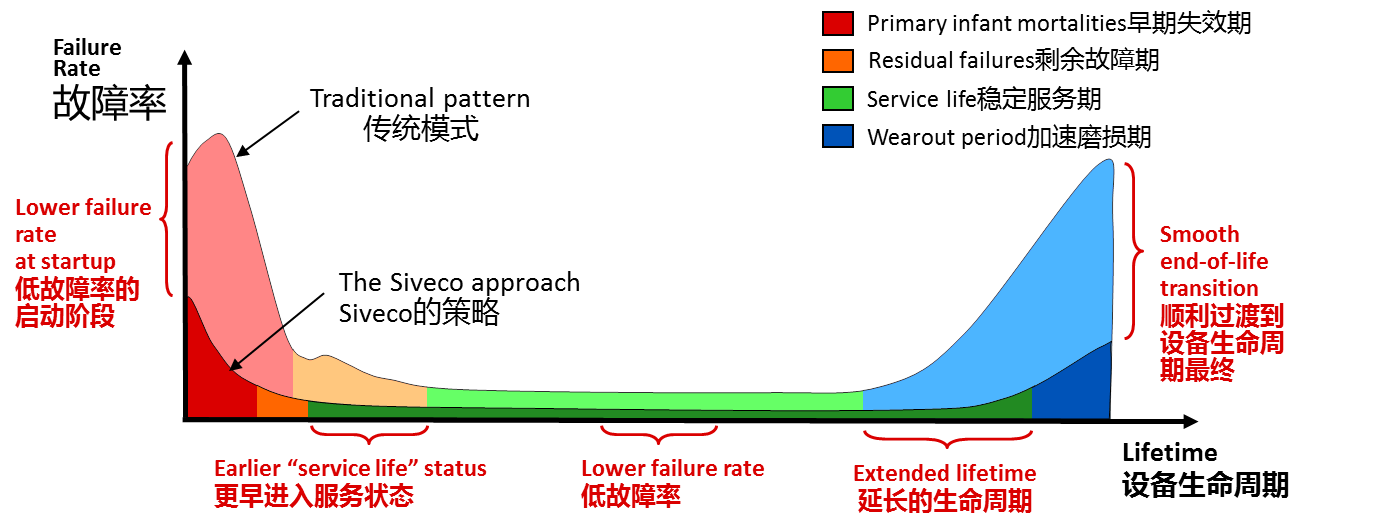

Exploring the bathtub curve

The “bathtub curve” maps the failure rate over time for complex electro-mechanical systems such as machines or plants. Its shape is the same all over the world, but certain characteristics of Chinese construction projects tend to result in a less optimized curve (shown as “traditional pattern” in the figure). Let us explore the bathtub curve!

Typical facility lifecycle in China

The bathtub curve consists of three periods: 1. the infant mortality period with a decreasing failure rate, 2. the normal or useful life period with a low, relatively constant failure rate and finally 3. the wear-out period with an increasing failure rate.

1.

The first period corresponds to the start-up phase, showing defects resulting from design, construction and installation problems. These are normally eliminated during commissioning. To meet the needs of the country’s development, Chinese construction has adopted a flexible approach to build faster and cheaper: design changes often happen onsite (e.g. change of material as the specified material is unavailable, different routing of cables or pipes…) and may not be documented. When infant problems occur, most contractors apply “quick-fixes” instead of identifying the root causes. This often results in bigger problems in later operations.

2.

As a direct consequence, the residual failure rate tends to be high. We have entered the second period, the “useful life” of a facility, during which the failure rate is stable. Due to residual failures, Chinese facilities tend to exhibit a higher failure rate than normal, often compounded by lack of preventive maintenance. This is sometimes hidden by the good reactivity of the repair teams (and contractor’s personnel left onsite during initial phase) and lack of statistical analysis by operation teams.

3.

A few years down the line, the breakdown rate constantly increases, characterizing the end-of-life period, when equipment eventually wears out. For plants and major systems, a useful life of 15-25 years is normal. Facilities however tend to age much faster in China, leading to early replacement of major equipment (transformers, diesel generators, boilers etc.), often hidden within extension projects (since constant expansion has so far been the norm in China).

We often observe a false end-of-life pattern, sometimes only a few years after startup. Reasons are not easy to identify as, in most cases, no reliable maintenance history (for example in the form of computerized records) is available to support improvement decisions. Studies show that most of these problems can be traced back to residual failures i.e. design and installations problems that were never addressed.

It is interesting to note that outsourcing maintenance to a third-party service supplier does not help, as more and more companies are finding out. These are engineering rather than execution problems. In fact, a third-party maintenance firm, not related to the owner, may be less capable of addressing such problems.

All this is not bad news. Chinese construction methods have proven extremely beneficial to the country’s unparalleled development. They have even inspired international construction groups for their own mega-projects. As China transitions to a more sustainable economy, dubbed the China Dream, the less optimized bathtub curve leaves many opportunities for improvement in all three periods. As shown in this article, the key is to act during the first period, construction, or at the very least to understand the overall pattern in order to take meaningful actions.

Tags: construction、bathtub curve