BIM for maintenance: smart… or not?

This paper was published by the Building Services Operation and Maintenance Executives Society (BSOMES) of Hong Kong in the proceedings of the 7th Greater Pearl River Delta (GPRD) Conference on Building Operation and Maintenance – “SMART Facilities Operation and Maintenance”, held on December 6, 2016 in Hong Kong. The original article (English only) can also be found on the BSOMES website at: http://www.bsomes.org.hk/upload_pdf/GPRD2016_S3-3.pdf.

Authors:

Bruno Lhopiteau (Managing Director, Siveco China) and Simon Ng (Associate Director, WSP Hong Kong)

Abstract

The use of “smart” BIM for O&M meets practical “dumb” challenges, especially in the Chinese market where maintenance practices are not well established. Useful lessons can however be learnt from experience and standards used in the industry. A project role must be created for O&M data preparation, first to define specifications, formats, schedules before major equipment contracts are signed, then to follow up data preparation activities during construction. As far as software is concerned, a practical advice is to avoid conflicts with project teams and software vendors: instead, an O&M layer added onto the BIM model can provide the necessary support. Examples of projects in environmental utilities and buildings in mainland China and Hongkong are given.

Keywords

BIM; maintenance; CMMS.

1 The armchair technician syndrome

As Building Information Modelling (BIM) is fast becoming mandatory for major construction projects, owners are considering how to use BIM to support operations and maintenance (O&M). Meanwhile, “BIM for Facilities Management” and other “Building Life-cycle BIM” have become hot topics at conferences all over the world.

Vendors, eager to sell more software licenses, tend to show unrealistic demos for “armchair technicians”, far removed from the daily reality of maintenance people. The typical scenario consists in navigating into a 3D model, sometimes using Virtual Reality goggles, selecting a specific piece of equipment and accessing related maintenance information, perhaps creating a “maintenance work order”. Numerous proof-of-concept projects based on this ill-conceived yet smart-looking approach have shown no real-life application.

Practical hurdles in data preparation have also impaired actual applications. In the Chinese market in particular, as-built drawings are seldom available to the building owner (if they exist at all), equipment suppliers may not have proper technical documentation and O&M practices are generally lacking (as shown in the “Maintenance in China” survey conducted by Shanghai University and Siveco). As a result, most BIM models remain “empty” from an O&M perspective and we often hear “smart” software vendors blaming “dumb” building technicians for their project failure.

2 Learning from the industry

As buildings grow higher and technically more complex, preparing O&M from the construction stage is becoming a necessity. Ultra-high buildings for example are more than just large concrete structures: they rely on a growing number of large-scale industrial systems (HVAC, water treatment, power supply, elevators etc.) that are akin to highly-automated process plants. Lessons can be obviously learnt from industrial experience.

It has been said before that BIM technology is nothing new: 3D design has been used in the aerospace industry and later in the process industry (oil & gas, chemicals, utilities) for decades. In the late 90s, one of the authors has worked with 3D modelling and data management tools (the term “BIM” had not been coined yet) integrated with Computerized Maintenance Management System(s) for applications in chemical plants. More than just technology, the practice of preparing maintenance data from the construction stage is well structured and widely implemented in this industry, a fact reflected in mature industrial standards.

More than a fad, the use of BIM as a tool to prepare O&M from the construction stage could be a powerful enabler for best practices in the changing building industry. To achieve this, the data preparation process should be specifically designed to overcome the obstacles usually met in construction projects, more specifically in Chinese construction. Furthermore, the usage scenario of BIM for O&M should be based on real-life maintenance needs, not on vendor’s dreams.

3 Handover from construction to O&M

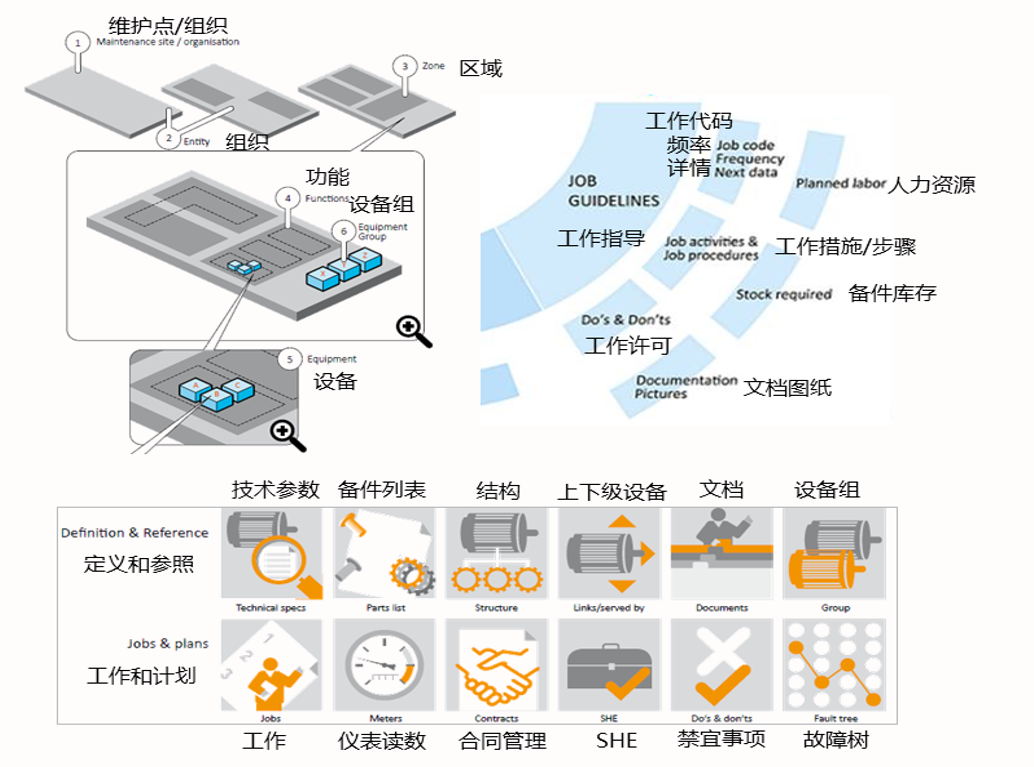

While the main focus of the BIM team is often to create vivid 3D representations of future buildings as a showcase for owners and officials, the graphical representation of the building present very little practical use for FM teams. In this regard, British Standard PAS 1192-2:2013 Specification for information management for the capital/delivery phase of construction projects using building information modelling offers useful insight. It describes a “Common Data Environment” containing all useful information for handover to operations, emphasizing the importance of non-graphical data and documentation.

Figure 1 – PAS 1192-2:2013 Common Data Environment

As for details of what actual data is required for operation, PAS 1192-2:2013 simply points to existing industrial standards (chiefly the ISO 55000 series on Asset Management, derived from its BSI antecedent PAS 55) and to established practices, which presents an interesting challenge for companies in the Chinese market, where existing maintenance practices remain weak.

More strikingly, better-known BIM standards such as the COBie data format or AIA’s LOD-500 provide remarkably little when it comes to O&M, which tends to show that the required know-how is not available in BIM circles. Instead, LOD-500 emphasizes the need for “as-built models with field verification, authorized for usage for O&M of the facility”, essentially kicking the ball to the operation team. BIM team are too often left to themselves trying to reinvent the wheel.

Industrial standards, unrelated to BIM and written by people without any knowledge of BIM, prove on the other hand to be extremely useful in practice. The most popular of them, ISO 55000, remains somewhat general, but other standards (such as EN 15331, EN 13460 and ISO 14224) provide immediately applicable guidance. Industry practitioners, especially those coming from the process industry and utility sector, will be familiar with those standards. In the past few years, we note increasing convergence between Facility Management standards and industrial maintenance standards, the former referring to the latter, which further demonstrates the authors’ view of “learning from the industry” when it comes to building operations.

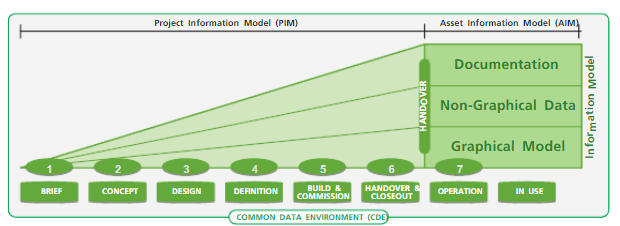

4 An overview of O&M data

Only once the data requirements are defined, based on international standards, can the question of the supporting IT tools be answered. BIM software itself cannot accommodate the required O&M data, which are not just a list of parameters but structured, complex, data, as shown in the figure below. Indeed, mapping between COBie and common BIM formats such as Revit® shows that complex data such as spare parts, preventive maintenance instructions, etc. cannot be easily stored inside the model itself.

PAS 1192-2 offers a simple answer: its proposed “Common Data Environment” is based on multiple software programs, not just BIM.

An increasingly common approach to this question is exemplified in the Shenzhen Municipality BIM standard (深圳市建筑工务署政府公共工程BIM应用实施纲要). This standard takes a predominantly technology-driven view, as opposed to the working process view of international standard, calling for integration between BIM and a variety of building systems (including BMS and CCTV). Some confusion occurs as to maintenance systems, perhaps reflecting influence from multiple software vendors, each with its own focus area such as space management, work management and asset management.

As seen with the “armchair technician”, overexcitement over technology indeed is one of the many pitfalls of such project: while technology offers many possibilities, basics (such as which data should be collected and how) have to be in place first, which the Shenzhen standard does not address.

5 Various software approaches to BIM for O&M

Various attempts at “multiple software” have been made. An early approach has been to develop additional features within the BIM software, often meeting technical challenges as complexity was often underestimated. To meet the limitations of BIM, database-driven middleware has been developed that connects the BIM model to third-party Asset Management functionalities running on a relational database. This approach is also fraught with risk, judging by the small number of international software vendors active in the maintenance market: established vendors have spent decades improving their software design and no new entrant has emerged since the late 1980s.

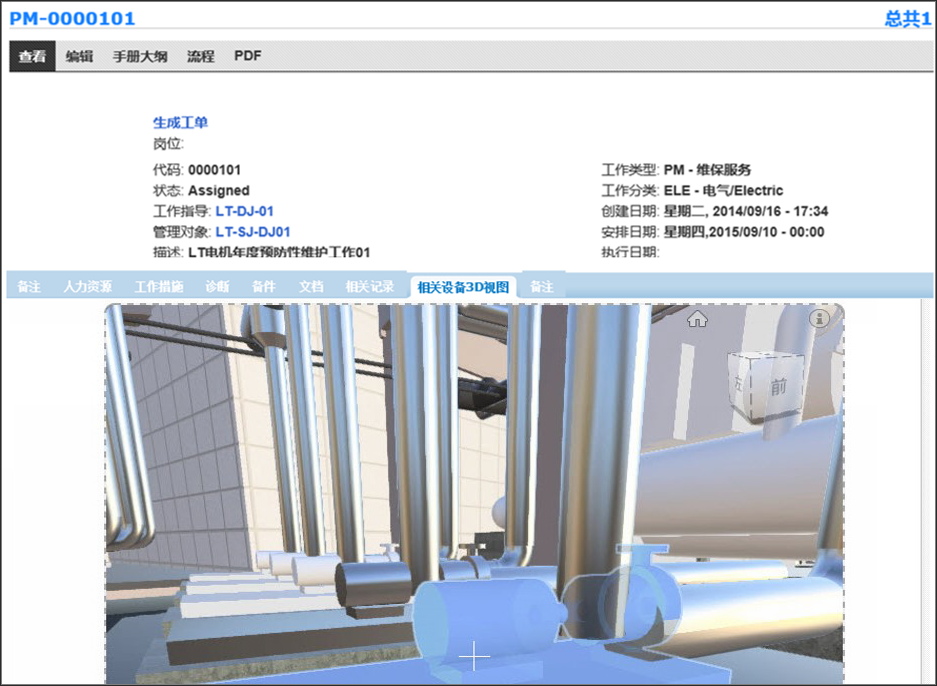

The obvious alternative is for BIM data to be reformatted and uploaded to a Computerized Maintenance Management System (CMMS). Some modern CMMS are then able to display 3D views by calling up a BIM viewer (this may require third-party interface modules or additional software development for interfacing, but is incomparably less complex than developing CMMS functionality). This approach has already been successful in the industry. It has however met implementation hurdles, as CMMS vendors usually work with O&M teams only after the building has been completed, as witnessed by the authors in hundreds of CMMS projects across Asia.

In the building industry, none of these solutions has shown very satisfactory yet: there have been remarkably few full-scale implementations, primarily due to external real-life factors that software vendors have little experience with. Chief amongst them: lack of O&M data provided during construction (usually due to limited experience among contractors and no specific contractual terms in place), O&M teams not involved during the project (for the obvious reason they come on board only years later), budget allocation issues and conflicting objectives between construction and O&M teams. As a result, among the many proof-of-concept projects announced in the past few years, very few have been used in day-to-day operations. More often than not, “smart” loses against “practical”.

6 Return from the fictitious to the real

In the words of Victor Hugo: “A revolution is a return from the fictitious to the real.” Especially for “revolutionary” projects such as BIM for O&M, the most down-to-earth approach often works best. The project approach and supporting software tools must address the real situation; the real situation can consequently not be blamed for project failure. Self-evident when it comes to civil engineering, lest buildings collapse, it is too often ignored in IT project.

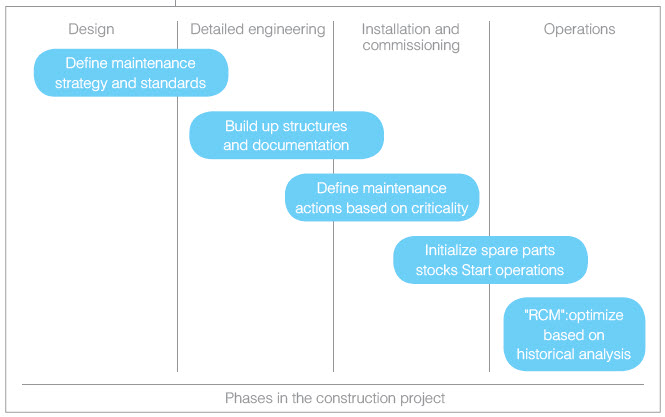

First of all, as shown in PAS 1192-2:2013, a role must be created, on the project owner’s side, for an engineer (or team of engineers) in charge of O&M data preparation. This role may be filled by a third-party specialist firm, a maintenance consultancy with relevant experience often acquired in the process industry rather than in the building industry for the reasons explained in the first section. The early stage of the project, ideally completed before major equipment contracts are signed, consists in defining detailed specifications, formats, roles and schedule for the data preparation. This will ensure that useful O&M data are provided by suppliers, in the right electronic format, while minimizing workload and costs. Data preparation activities then follow the entire construction project, during which suppliers submit documentation as required and appointed contractors check and package data for delivery to the owner as as-built O&M documentation.

As far as software is concerned, a practical advice is to let design and construction teams choose their BIM software and to let O&M or FM teams chose their operation management tool. The latter comes much later in the life of the building, ideally still before opening, but sometimes years later considering the time and budget constraints of building operations. By carefully avoiding conflicts with established IT practices and software vendors, the O&M data preparation project will then be able to start.

Instead, an add-on O&M layer on the BIM model can provide support to build up O&M data directly connected to the BIM, as illustrated by the case studies in the next section of the article. Somewhat similar to the middleware approach described above, this data preparation tool must however offer specific support for facilitating the data collection effort, ensuring consistency checks, checks against coding rules, progress monitoring etc. It should allow linking between the BIM and O&M data, with effortless graphical user interface navigation between them. Subsequently when the building enters its service life, the O&M team can continue to access data as required directly from the BIM, via the O&M layer, or opt to transfer all data to a CMMS, whenever the CMMS is ready. This win-win approach brings benefits to all involved, construction and operation teams, BIM and CMMS vendors.

Figure 3 – Siveco’s bluebee® cloud O&M data preparation tool

7 Real life experience

This pragmatic approach combining industrial maintenance experience and no-nonsense software support has been applied with success in a number of projects in mainland China and Hong Kong.

Siveco China has assisted environmental utility group Suez in O&M data preparation during the construction of its hazardous waste–to energy recovery plant located in Nantong, Jiangsu province. The plant started operations in late 2015, using Siveco software to run its day-to-day maintenance. The 3D model was not used in this project, as it did not contain useful data. The same strategy is currently being used for Hong Kong’s Organic Waste Treatment Facility, currently under construction by Suez and its local joint-venture partner Atal Engineering on North Lantau Island, for which the 3D model will be linked to O&M data.

Figure 4 – Preparing maintenance from the construction stage

China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) has deployed Siveco’s bluebee® cloud solution for its new Beijing office complex. The system acts as a maintenance data repository linked to a Revit® BIM model to showcase the utilization of BIM in Facility Management. CNOOC is considering extending usage of the system to its other real estate properties. The same software solution is currently being used for a 530m high building under construction in Tianjin.

While Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District Authority (WKCDA) is considering selecting a Facility Management System when the whole district comes to completion 10 years later, its first building, the M+ Pavilion, was completed in 2016 for the pilot use of small scale arts exhibition. How to build the O&M database and extract relevant information from the BIM model of this building and later pass it to the future FM system? BIM consultant WSP|PB worked closely with the project team, contractor and FM team to develop O&M data and BIM equipment lists in COBie format. These COBie data, in Excel format, stored in the Common Data Environment (CDE), will be the most flexible way to transition to the future FM system, no matter which system is chosen and when it will be deployed.

For more on Siveco’s approach to BIM for Asset Management also see: http://www.sivecochina.com/en/products/bim-for-asset-management or contact info@sivecochina.com with your questions.

8 Acknowledgments

Figure 1 copyright by Mervyn Richards

Figures 2-4 copyright by Siveco Group

Revit® is a trademark of Autodesk

bluebee® is a trademark of Siveco Group